Time and time again, people try to solve Mars. They suggest a radical solution, or some neat operating trick, that they claim makes the whole problem of exploration and settlement wildly easier. Many of these people are very smart and many of their ideas are genuinely insightful and unexpected. Unfortunately, in an overwhelming majority of cases, they aren’t helpful. If we could crack Mars open with a clever solution, or design the perfect settlement on paper, we would have done it by now. No – the reason we haven’t solved the problem of Mars yet is that Mars isn’t the kind of problem that has a solution. Yet.

“The solution to the problem of Mars” is an almost nonsensical statement when you write it out. It almost rivals the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything. As soon as you hear it, it starts to spawn new questions. What problem? Who’s decided what is the most important part of the challenge? Has anyone done that? How are we defining a solution? What criteria have we met to declare the problem solved? Does the problem include some end state, which we can achieve and be finished? Is that a sensible way to go about defining problems in the first place?

Of course, I’m being deliberately a little oblique here. Most people don’t claim to have solved the entirety of Martian settlement in perpetuity with their new habitat construction system. In the same way, most political theorists on Earth don’t claim to have solved the entire mess with their new way of thinking about things. They claim to have tackled – as they see it – an outstanding inefficiency in the current plan. They see a scheme for exploration and settlement, see an addressable flaw, fix the flaw. I spend a good deal of my time thinking about Mars at this level – because frankly, solving technical problems is fun! But a few people step back and ask harder – is this a sensible plan in the first place? And even fewer step all the way back and ask, what are we using to design this plan? Not what is the plan, but why is the plan?

That is the real problem of Mars. We have plans, but we very very rarely ask why those plans are the way they are. Until we can answer why the plan, we’re going to be stumbling around what the plan is. And you can throw out any hope of tweaking the fine details of any particular plan. At best it’s balanced on a pile of assumptions, at worst it’s a vague mess.

There is one highly notable exception. In 1990 Robert Zubrin and David Baker looked at the hulking SEI proposal to send people to Mars with a $450 billion price tag, and asked why. With their Mars Direct proposal they inverted the entire establishment’s thinking about the point of Mars exploration. The purpose should be boots on Mars, as cheaply and as quickly as possible, they said. The purpose should not be technology stack maximisation. This way of thinking has been beyond successful – it forms the basis of NASA’s Reference Design Missions, it is the plot of dozens of science fiction stories, it is the starting point of SpaceX’s Mars mission.

SpaceX’s Problem

Let’s make this less philosophical and take an example. Elon Musk says he wants a city on Mars in his lifetime – probably by 2075 or thereabouts. It’s easy to say “that’s a silly idea” and even easier to say “that’s a poorly defined idea” – because the latter is probably true. But – why a city? What does city mean? What’s the end goal – is the city a means to an end, or an end unto itself? What are you trying to achieve here, in the broadest possible sense? “Making life multiplanetary” is an awesome mission statement but in this case it cries out for clarification. Maximising human population in space ASAP, in the event of global catastrophe? Building the most capable industrial system as fast as possible to allow for expansion into the solar system? A utopian society with a fresh start? Elon, what do you want?

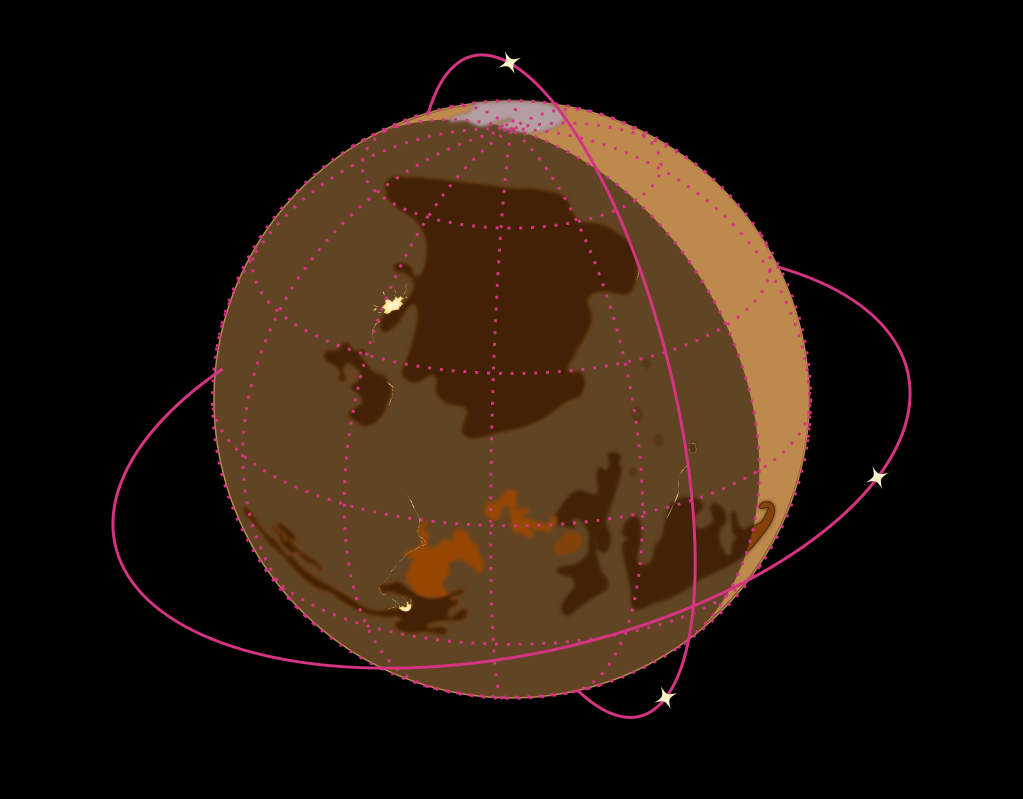

That is why, if you ask me, SpaceX doesn’t have a coherent vision for Mars. They haven’t yet decided – because it’s a damn hard problem! – what they want. This is an underlying issue that goes beyond any kind of mission parameter. Maybe the city will be equatorial or at a high-latitude glacier, maybe it will be entirely underground or sprawling on the surface. None of that matters. For now, the city has no purpose.

That presents a very real problem for SpaceX. The Starship program is too big for doing anything but large-scale exploration and settlement. The initial boots-and-flags architecture requires “just” 2-3 ships across 5 years with a Mars semi-Direct architecture – far below the planned cadence of the construction yards at Boca Chica and the Cape. There is currently a gap between the payload capacity to Mars and the availability of payload (something we’re trying our best to solve at Nexus Aurora!). Unlike hardware for those very first exploration missions, this isn’t a problem that can be easily solved with focused application of regular engineering and design. SpaceX don’t know what they want from a Mars city; they can’t tell the good folks at Pioneer Astronautics what they want in the payload bay; no payload is designed; the ships don’t fly. Until this is cleared up we either have no city at all, or a hodge-podge of competing and conflicting designs on the Martian surface. Both bad outcomes.

The problem that needs solving

We don’t need another habitat design, or another way to drill for water ice. We need someone to devise a really compelling “why” for Mars settlement. We need a bold target, a vision, a guiding beacon. Once we know why we’re doing it, we can determine what we’re doing – first in broad strokes, then in detail, then with hardware, then with people. Are we trying to get people on Mars as fast as possible? As cheaply? Do we want to build the most capable industrial stack? A wide one (capable of crude production in huge volume) or a tall one (capable of highly sophisticated manufacture but not at scale)? How does Mars fit into broader plans for the solar system? Is Mars merely a means to an end of wholesale expansionism? What role do scientists and preservationists play? Do we come here to build, to grow, to learn?

Don’t start with a design. Designs change, circumstances change, geotechnical reality will mess with any fast ones you try to pull. Start with the vision. Ask why, then what, then how, then when.

6 replies on “Mars is not a “solutions” problem”

The main reason for the Mars mission is to get boots on the ground and bring the science lab to the planet rather than tiny samples maybe returning back to earth while the rovers scratch away on the surface.

The second reason for the initial mission is to gauge how feasible a potential permanent science station is on the planet. Can NASA astronauts live there feasibly for a year plus?

Only once those two are accomplished can future plans for a colony be developed. The big “why factor” is seeing if it is even possible.

For SpaceX , missions landing on Mars, (even unmanned ones,) will set them apart entirely from other companies.

Everyone on the planet would benefit from tagging along or setting off on their own future Mars missions. Even just a permanent 5-10 human presence on Mars would be such a boon for STEM programs. A Moon base AND Mars? That’s fucking awesome. That’s why we should go. And if by chance we discover past organic life… all bets are off.

Anyways, I’m just an armchair enthusiast. Good article.

When the [insert migrants here] set out to towards the horizon they didn’t have a bigger mission statement, probably, than “it is maybe less crowded over there”. Maybe they where looking for something better. Anything off planet is probably not going to be better for most people, for a very long time.

Despite that, I think a bigger purpose is needed. Turning our society into a sustainable one, working with the ecology is key, but that won’t take all the resources or minds. Lifting the eye above the horizon will attract many, and sustainable circular systems on Earth are nice and probably required in the future, but they are definitely required off Earth. Once you crack the nut of energy, and resources off Earth, society can grow very big indeed and reach very far.

I work on a little corner of it, but Kim Stanley Robinson describes it better. The populated solar system. We can and we should. It doesn’t need to be the shitshow of the Expanse. Let’s not mess it up, so let’s do something good.

Very nicely put – and I strongly agree with the narrative of “space forces us to build the systems required for a long-term sustainable future on Earth”. It’s a vision that makes sense to everyone I speak to outside the space settlement bubble.

The only point I would quibble with is the comparison to historic waves of migration/settlement on Earth. While the northeast coast of America, the edges of Australia or the various Pacific islands are substantially different to the climate/environment of Europe, they are survivable by a medium-size group of skilled individuals by transferring knowledge about agriculture etc. A better analog for a colonial-era Mars expedition is something like the Darien Scheme – Scotland’s attempt to found a colony in Panama. Between poor planning and understanding of the environment, and some hostility with other powers, it drained 20% of all the wealth in the country and was a major contributor to Scotland joining the UK in 1707. We cannot afford a parallel in the 21st century.

Mr. Ross — thanks for a thoughtful and interesting article. But I don’t agree. There are certainly many technical challenges to be overcome on the path to a permanent establishment on Mars, some of which Elon and others may be underestimating, some which are likely to be completely unknown until we are confronted by them. And for now it is true the admirable and creative design efforts being made by Nexus Aurora and others are a bit scattershot, lacking a full understanding of those challenges from an engineering point-of-view and, as you note, a clear purpose. But to demand a well-defined ’why’ is a path to paralysis.

There is a massive amount of goal-directed research pursued by a multitude of commercial and publicly funded organizations around the world. But national governments, especially, fund basic research efforts in every field with no clear future benefit, or even a goal beyond increasing our knowledge, in the belief that the applications, the benefits, will come. And humanity, in my view, has been well-served by these efforts. When we first ventured to space, the ostensible purposes seems to have been prestige and military superiority (or perhaps, fear of inferiority), and later, commercial spin-offs. But the fuller potential of near-Earth space has become appreciated gradually and is only now being realized, over 60 years after Sputnik. Many might think that it would have been different had we had a well-defined goal but the U.S. had one with Apollo and as essential as it was in demonstrating it could be done, it proved to be not enough by itself. Even though each individual project required remarkable technological prowess and organizational, the overall course of the push into space has been messy, with many pauses, mistakes, and redirects along the way. I believe that’s the way it has to be, always has been, and always will be whenever we seek to explore new frontiers, whether they be physical or in our understanding.

As for Mars, agreement on a specific purpose beyond the grand vision of expanding human knowledge and reach will require a political and social consensus that is hard to come by in the best of times, and likely impossible in the present. As it is, there are many reasons to go to Mars, or beyond Earth in general — development of engineering capability, a hedge against extinction, national glory (and the soft power that comes with it), inspiration and elevation of the human spirit, achieving a manifest destiny. And to realize these goals, there are many routes. Pick one, any one. Better yet, pick them all. Prepare as best we can, but we will figure things out as we go. No matter how carefully we plan or justify, we will probably find that the best designs and the best reasons for being there, in the end, will be quite different from those we started with. So, yes, let’s get boots on Mars as cheaply and as quickly as we can and find out what it takes to get there and be there. Let’s just go!

Great Article!

My “vision” or “purpose” that drives me towards settling Mars permanently is the existential concern I have that we, humanity, may only have one shot at this.

If we are unable to get to Mars in our lifetimes it may be that it becomes impossible for humans to ever leave Earth.

We may only have these next few decades before the window of opportunity for humanity to leave Earth closes forever.

“It’s easy to say “that’s a silly idea” and even easier to say “that’s a poorly defined idea” – because the latter is probably true. But – why a city? What does city mean? What’s the end goal – is the city a means to an end, or an end unto itself? What are you trying to achieve here, in the broadest possible sense? ”

Not sure why this is such a mystery, Elon Musk has clarified this numerous times, see this for example: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/elon-musk-mars-spacex-starship-colony-b1179088.html

So what does a city mean? It means a self-sufficient/self-sustaining Mars colony. He only called it a “City” because for various reasons the word “colony” or “settlement” is no longer politically correct.

As Elon said, the test case for this is very simple: Can your colony survive (and thrive) if resupply from Earth stopped? If it can, then congratulations, you have achieved the goal.